An original Harvey Ball smiley face (image: The World Smiley Foundation)

In the 1994 Robert Zemeckis film, Forrest Gump stumbles into the history books as he runs across the country.

At one point, he meets a poor T-shirt salesman who, Gump recalls, “wanted to put my face on a T-shirt but he couldn’t draw that well and he didn’t have a camera.” As luck would have it, a truck drives by and splashes Gump’s face with mud. He wipes his face on a yellow T-shirt and hands it back to the down-on-his-luck entrepreneur, telling him to “have a nice day.” The imprint of Gump’s face left a perfect, abstract smiling face on the bright yellow t-shirt. And thus, an icon was born.

As you probably expect, that was not how the iconic smiley face was created. There was no cross-country runner or struggling t-shirt salesman, there was no truck or mud puddle. There was, however, a graphic designer, some devious salesmen, and an ambitious newspaper man – all add up to a surprisingly complex history for such a simple graphic.

It’s largely accepted that the original version of the familiar smiley face was first created 50 years ago in Worcester, Massachusetts by the late Harvey Ross Ball, an American graphic artist and ad man. Ball came up with the image in 1963 when he was commissioned to create a graphic to raise morale among the employees of an insurance company after a series of difficult mergers and acquisitions. Ball finished the design in less than 10 minutes and was paid $45 for his work. The State Mutual Life Assurance Company (now Allmerica Financial Corporation) made posters, buttons, and signs adorned with the jaundiced grin in the attempt to get their employees to smile more. It’s uncertain whether or not the new logo boosted morale, but the smiling face was an immediate hit and the company produced thousands of buttons. The image proliferated and was of course endlessly imitated but according to Bill Wallace, Executive Director of the Worcester Historical Museum, the authentic Harvey Ball-designed smiley face could always be identified by its distinguishing features: the eyes are narrow ovals, one larger than the other, and the mouth is not a perfect arc but “almost like a Mona Lisa Mouth.”

Neither Ball nor State Mutual tried to trademark or copyright the design. Although it seems clear that Ball has the strongest claim to the second most iconic smile in history, there’s much more to the story.

Harvey Ball’s smiley pin for The State Mutual Life Assurance Company (image: The Smiley Company)

In the early 1970s, brothers Bernard and Murray Spain, owners of two Hallmark card shops in Philadelphia, came across the image in a button shop, noticed that it was incredibly popular, and simply appropriated it. They knew that Harvey Ball came up with the design in the 1960s but after adding the the slogan “Have a Happy Day” to the smile, the Brothers Spain were able to copyright the revised mark in 1971, and immediately began producing their own novelty items. By the end of the year they had sold more than 50 million buttons and countless other products, turning a profit while attempting to help return a nation’s optimism during the Vietnam War (or provide soldiers with ironic ornament for their helmets). Despite their acknowledgment of Harvey’s design, the brothers publicly took credit for icon in 1971 when they appeared on the television show “What’s My Line.”

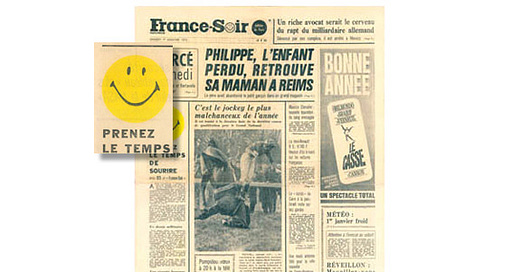

The smiley used to highlight good news in the newspaper France Soir (image: The Smiley Company)

In Europe, there is another claimant to the smiley. In 1972 French journalist Franklin Loufrani became the first person to register the mark for commercial use when he started using it to highlight the rare instances of good news in the newspaper France Soir. Subsequently, he trademarked the smile, dubbed simply “Smiley,” in over 100 countries and launched the Smiley Company by selling smiley T-shirt transfers.

In 1996, Loufrani’s son Nicolas took over the family business and transformed it into an empire. He formalized the mark with a style guide and further distributed it through global licensing agreements including, perhaps most notably, some of the earliest graphic emoticons. Today, the Smiley Company makes more than $130 million a year and is one of the top 100 licensing companies of the world. The company has taken a simple graphic gesture and transformed it into an enormous business as well as a corporate ideology that places a premium on “positivity.” As for the American origin of the smiley, Nicolas Loufrani is skeptical of Harvey’s claim on the design even though, as evident in the above image, his father’s original newspaper icon is almost identical to Ball’s mark, idiosyncrasies and all. Loufrani argues that the design of the smiley is so basic it can’t be credited to anyone. On his company’s website, they prove this idea by showing what they claim to be the world’s first smiley face, a stone carving found in a French cave that dates to 2500 BC, as well as a smiley face graphic used for promotion by a New York radio station in 1960.

Copyright and trademark issues are complicated, and despite their views toward Ball’s design, when the Smiley Company attempted to trademark the image in the United States in 1997, they became embroiled in a legal battle with Walmart, which started using the smiley face as a corporate logo in 1996 and tried to claim ownership of it (because of course they did.) The law suit lasted 10 years and cost both companies millions of dollars. It was settled out of court in 2007 but its terms remain undisclosed.

In 2001, Charlie Ball tried to reclaim the optimistic legacy of his father’s creation from unbridled commercialization by starting the World Smile Foundation, which donates money to grass-roots charitable efforts that otherwise receive little attention or funding.

The cover to Watchmen No. 1, written by Alan Moore and illustrated by David Gibbons (published by DC Comics)

The simple yellow smiley face created in 1963 (probably) has led to tens of thousands of variations and has appeared on everything from pillows and posters to perfume and pop art. Its meaning has changed with social and cultural values: from the optimistic message of a 1960s insurance company, to commercialized logo, to an ironic fashion statement, to a symbol of rave culture imprinted on ecstasy pills, to a wordless expression of emotions in text messages. In the groundbreaking comic Watchmen, a blood-stained smiley face motif serves as something of a critique of American politics in a dystopian world featuring depressed and traumatized superheroes. Perhaps Watchman artist Dave Gibbons best explains the mystique of the smiley: “It’s just a yellow field with three marks on it. It couldn’t be more simple. And so to that degree, it’s empty. It’s ready for meaning. If you put it in a nursery setting…It fits in well. If you take it and put it on a riot policeman’s gas mask, then it becomes something completely different.”

Sources:

“Smiley’s People,” BBC Radio, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01bh91h; Smiley Company, http://www.smileycompany.com/shop/; Thomas Crampton, “Smiley Face is Serious to Company,” The New York Times (July 5, 2006); “Harvey Ball,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harvey_Ball